Architecture¶

Overview¶

To be run by the CloudSlang Orchestration Engine (Score), a CloudSlang

source file must undergo a process to transform it into a Score

ExecutionPlan using the SlangCompiler.

Precompilation¶

In the precompilation process, the source file is loaded, along with its

dependencies if necessary, and parsed. The CloudSlang

file’s YAML structure is translated into Java maps by the YamlParser

using snakeyaml. The parsed structure is

then modeled to Java objects representing the parts of a flow and

operation by the SlangModeller and the ExecutableBuilder. The

result of this process is an object of type Executable.

Compilation¶

The resulting Executable object, along with its dependent

Executable objects, are then passed to the ScoreCompiler for

compilation. An ExecutionPlan

is created from the Executable using the ExecutionPlanBuilder.

The ExecutionPlanBuilder uses the ExecutionStepFactory to

manufacture the appropriate Score ExecutionStep objects and add

them to the resulting ExecutionPlan, which is then

packaged with its dependent ExecutionPlan objects into a

CompilationArtifact.

Running¶

Now that the CloudSlang source has been fully transformed into an

ExecutionPlan it can be run using Score. The

ExecutionPlan and its

dependencies are extracted from the CompilationArtifact and used to

create a TriggeringProperties

object. A RunEnvironment is also created and

added to the TriggeringProperties

context. The RunEnvironment provides services

to the ExecutionPlan as it

runs, such as keeping track of the context stack and next step position.

Treatment of Flows and Operations¶

Generally, CloudSlang treats flows and operations similarly.

Flows and operations both:

- Receive inputs, produce outputs, and have navigation logic.

- Can be called by a flow’s step.

- Are compiled to

ExecutionPlans that can be run by Score.

Scoped Contexts¶

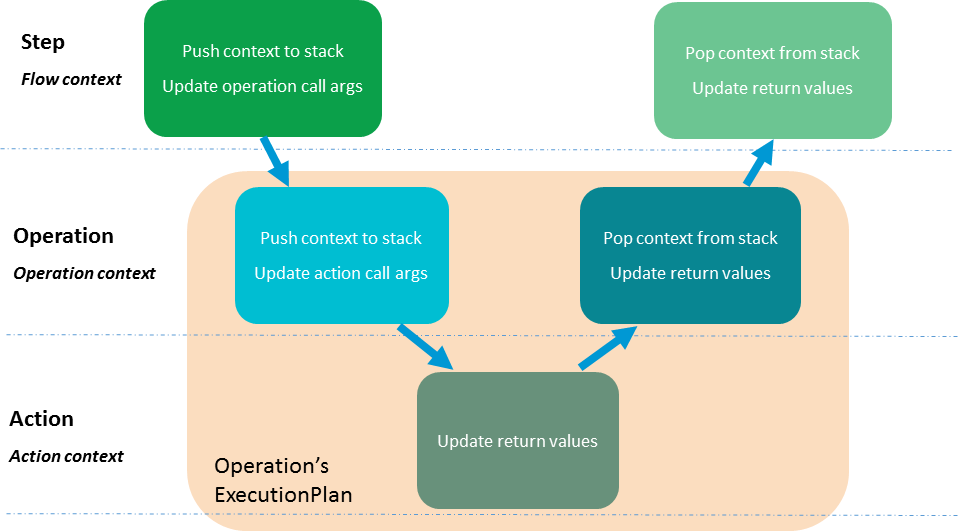

As execution progresses from flow to operation to action, the step data

(inputs, outputs, etc.) that is in scope changes. These contexts are

stored in the contextStack of the

RunEnvironment and get pushed onto and popped

off as the scope changes.

There are three types of scoped contexts:

- Flow context

- Operation context

- Action context

Value Types¶

Each Context stores its data in a Map<String, Value> named

variables, where Value declares the isSensitive() method and is one

of three value types:

SimpleValueSensitiveValuePyObjectValue

SimpleValue is used for non-sensitive inputs, outputs and arguments.

SensitiveValue is used for sensitive inputs, outputs and arguments.

Calling the toString() method on a SensitiveValue will return the

SENSITIVE_VALUE_MASK (********) instead of its content. During runtime,

a SensitiveValue is decrypted upon usage and then encrypted again.

PyObjectValue is an interface which extends Value, adding the

isAccessed() method. An object of this type is a (Javassist) proxy,

which extends a given PyObject instance and implements the PyObjectValue

interface. Value method calls are delegated to an inner Value instance,

which can be either a SimpleValue or SensitiveValue. PyObject method

calls are delegated to an inner PyObject, the original one this object is

extending. PyObject method calls also change an accessed flag to true.

This flag indicates whether the value was used in a Python script.

Value types, SimpleValue or SensitiveValue are propagated automatically

from inputs to arguments and Python expression evaluation outputs. An argument

or output is sensitive if at least one part of it is sensitive. For example, the

result of a + b or some_func(a) will be sensitive if a is sensitive.

Before running a Python expression all the arguments which are passed to it are

converted to PyObjectValue. When the expression finishes, all the arguments

are checked. If at least one sensitive argument was used the output will be

sensitive as well.

As opposed to expressions, the output types of Java and Python operations, are not propagated automatically to the operation’s outputs. Doing so would cause all outputs of an operation to be sensitive every time at least one input was sensitive. Instead, none of the operation’s action’s data appears in the logs and a content author explicitly marks an operation’s outputs as sensitive when needed. This approach ensures that sensitive data is hidden at all times while still allowing for full control over which operation outputs are sensitive and which are not.

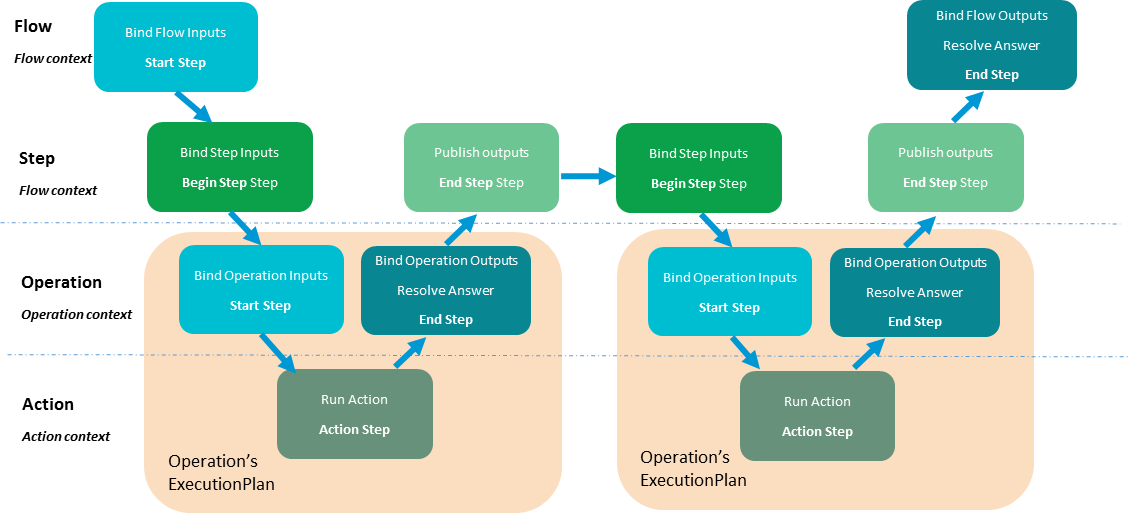

Types of ExecutionSteps¶

As flows and operations are compiled, they are broken down into a number

of ExecutionSteps. These

steps are built using their corresponding methods in the

ExecutionStepFactory.

There are five types of ExecutionSteps used to build a CloudSlang ExecutionPlan:

- Start

- End

- Begin Step

- End Step

- Action

An operation’s ExecutionPlan is built from a Start step, an Action step and an End step.

A flow’s ExecutionPlan is

built from a Start step, a series of Begin Step steps and End Step

steps, and an End step. Each step’s ExecutionSteps hand off the

execution to other ExecutionPlan objects representing

operations or subflows.

RunEnvironment¶

The RunEnvironment provides services to the

ExecutionPlan as it is

running. The different types of execution steps read from, write

to and update the environment.

The RunEnvironment contains:

- callArguments - call arguments of the current step

- returnValues - return values for the current step

- nextStepPosition - position of the next step

- contextStack - stack of contexts of the parent scopes

- parentFlowStack - stack of the parent flows’ data

- executionPath - path of the current execution

- systemProperties - system properties

- serializableDataMap - serializable data that is common to the entire run

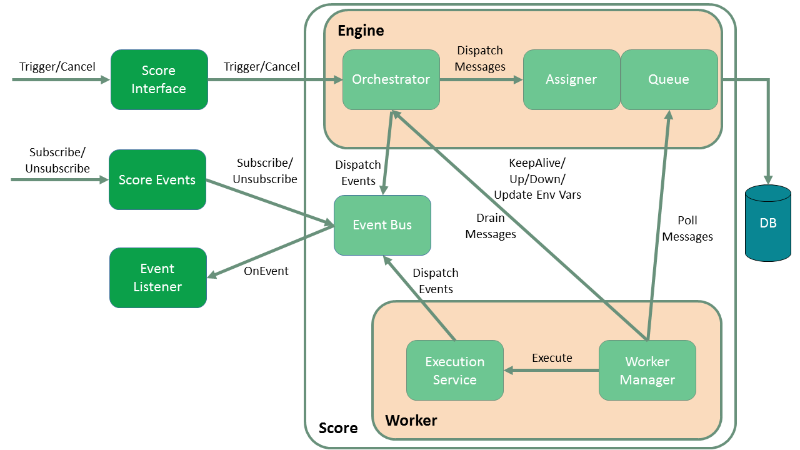

Engine Architecture¶

The CloudSlang Orchestration Engine (Score) is built from two main components, an engine and a worker. Scaling is achieved by adding additional workers and/or engines.

Engine¶

The engine is responsible for managing the workers and interacting with the database. It does not hold any state information itself.

The engine is composed of the following components:

- Orchestrator: Responsible for creating new executions, canceling existing executions, providing the status of existing executions and managing the split/join mechanism.

- Assigner: Responsible for assigning workers to executions.

- Queue: Responsible for storing execution information in the database and responding with messages to polling workers.

Worker¶

The worker is responsible for doing the actual work of running the execution plans. The worker holds the state of an execution as it is running.

The worker is composed of the following components:

- Worker Manager: Responsible for retrieving messages from the queue and placing them in the in-buffer, delegating messages to the execution service, draining messages from the out-buffer to the orchestrator and updating the engine as to the worker’s status.

- Execution Service: Responsible for executing the execution steps, pausing and canceling executions, splitting executions and dispatching relevant events.

Database¶

The database is composed of the following tables categorized here by their main functions:

- Execution tracking:

- RUNNING_EXECUTION_PLANS: full data of an execution plan and all of its dependencies

- EXECUTION_STATE: run statuses of an execution

- EXECUTION_QUEUE_1: metadata of execution message

- EXECUTION_STATES_1 and EXECUTION_STATES_2: full payloads of execution messages

- Splitting and joining executions:

- SUSPENDED_EXECUTIONS: executions that have been split

- FINISHED_BRANCHES: finished branches of a split execution

- Worker information:

- WORKER_NODES: info of individual workers

- WORKER_GROUPS: info of worker groups

- Recovery:

- WORKER_LOCKS: row to lock on during recovery process

- VERSION_COUNTERS: version numbers for testing responsiveness

Typical Execution Path¶

In a typical execution the orchestrator receives an

ExecutionPlan along with all

that is needed to run it in a

TriggeringProperties

object through a call to the Score interface’s trigger method.

The orchestrator inserts the full

ExecutionPlan with all of its

dependencies into the RUNNING_EXECUTION_PLANS table. An

Execution object is then created based on the

TriggeringProperties

and an EXECUTION_STATE record is inserted indicating that the

execution is running. The Execution object is then wrapped into an

ExecutionMessage. The assigner assigns the ExecutionMessage

to a worker and places the message metadata into the

EXECUTION_QUEUE_1 table and its Payload into the active

EXECUTION_STATES table.

The worker manager constantly polls the queue to see if there

are any ExecutionMessages that have been assigned to it. As

ExecutionMessages are found, the worker acknowledges that they

were received, wraps them as SimpleExecutionRunnables and submits

them to the execution service. When a thread is available from the

execution service’s pool the execution will run one step (control

action and navigation action) at a time until there is a reason for it

to stop. There are various reasons for a execution to stop running on

the worker and return to the engine including: the execution is

finished, is about to split or it is taking too long. Once an execution

is stopped it is placed on the out-buffer which is periodically drained

back to the engine.

If the execution is finished, the engine fires a

SCORE_FINISHED_EVENT and removes the execution’s information from

all of the execution tables in the database.

Splitting and Joining Executions¶

Before running each step, a worker checks to see if the step to be run

is a split step. If it is a split step, the worker creates a list of the

split executions. It puts the execution along with all its split

executions into a SplitMessage which is placed on the out-buffer.

After draining, the orchestrator’s split-join service takes care of the

executions until they are to be rejoined. The service places the parent

execution into the SUSPENDED_EXECUTIONS table with a count of how

many branches it has been split into. Executions are created for

the split branches and placed on the queue. From there, they are picked

up as usual by workers and when they are finished they are added to the

FINISHED_BRANCHES table. Periodically, a job runs to see if the

number of branches that have finished are equal to the number of

branches the original execution was split into. Once all the branches

are finished the original execution can be placed back onto the queue to

be picked up again by a worker.

Recovery¶

The recovery mechanism allows Score to recover from situations that would cause a loss of data otherwise. The recovery mechanism guarantees that each step of an execution plan will be run, but does not guarantee that it will be run only once. The most common recovery situations are outlined below.

Lost Worker¶

To prevent the loss of data from a worker that is no longer responsive

the recovery mechanism does the following. Each worker continually

reports their active status to the engine which stores a reporting

version number for the worker in the WORKER_NODES table.

Periodically a recovery job runs and sees which workers’ reported

version numbers are outdated, indicating that they have not been

reporting back. The non-responsive workers’ records in the queue get

reassigned to other workers that pick up from the last known step that

was executed.

Worker Restart¶

To prevent the loss of data from a worker that has been restarted additional measures must be taken. The restarted worker will report that it is active, so the recovery job will not know to reassign the executions that were lost when it was restarted. Therefore, every time a worker has been started an internal recovery is done. The worker’s buffers are cleaned and the worker reports to the engine that it is starting up. The engine then checks the queue to see if that worker has anything that’s already on the queue. Whatever is found is passed on to a different worker while the restarted one finishes starting up before polling for new messages.